Should hospitals embrace 3D printing for surgery?

By Atanu Chaudhuri, March 2021

.png)

A child is diagnosed with a congenital heart ailment. Surgeons are wary that the complex procedure needed will be too risky for the child to undertake. Another patient with a bone tumour in her left leg is waiting for her surgery date, but surgeons are not available as they are on Covid-19 duty. Another facial reconstruction (maxillofacial) surgery is also delayed due to lack of availability of implants.

These are not isolated cases. Many such patients have to wait due to lack of operating theatre capacity, non-availability of surgeons, lack of availability of implants, or because of the complexity and risk associated with such procedures. Covid-19 has exacerbated the situation and, unless they are extremely critical, many surgeries are delayed.

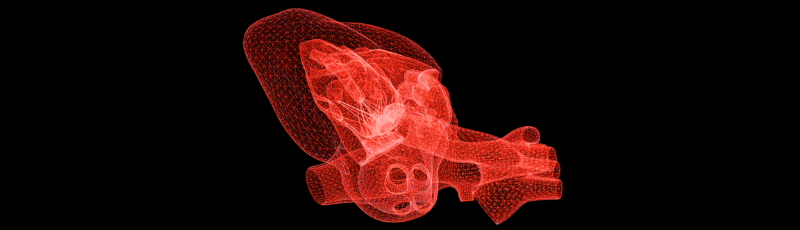

Complex surgical procedures require years of experience. The current practice for training and planning of difficult surgery cases has been through the use of cadaver models, which are not readily accessible. The cadavers also lack the patient-specific details that are very helpful for surgeons. Printing a three-dimensional model based on merging computed tomography (CT) and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) files, segmented from an individual patient, provides lots of detailed and exact information for the surgeon to plan the surgery accurately.

Complex surgery

Some complex surgeries also require implants to be fitted to the patients, but the implants are usually not customised for an individual patient, which can lead to post-surgical complications and longer recovery times. Complex surgeries also require long operation times, and therefore fewer patients can be operated on during a single day.

Surgical planning using 3D printed anatomical models allows for detailed planning of the surgery, which, along with customised 3D printed surgical guides and implants, alleviates many of the above problems, thereby improving both clinical outcomes for patients as well as efficiency for hospitals. The 3D printed anatomical model facilitates clearer communication between members of the surgical team and avoids surprises in the operating theatre. It can also help in communicating with the patient, thereby increasing the patient’s confidence in the procedure. Moreover, 3D printing provides tremendous opportunities for training surgeons and can shorten their learning curves.

The use of 3D printed anatomical models, as well as patient-specific customised surgical guides and implants, is gaining momentum across the world. In the UK, some NHS trusts, such as Royal Brompton and Harefield, already use them for congenital heart diseases. Similarly, surgeons at Guy’s and St Thomas’ had 3D printed a patient’s cancerous prostate and could plan the most precise robotic removal.

3D printing for surgeries

Research by myself and colleagues found that some hospitals across the world are developing internal capabilities by training junior resident surgeons in 3D modelling skills, while others have invested in a point-of-care 3D printing facility inside the hospital, which is operated and managed by service providers. The service providers work in close consultation with surgeons, while others may decide to outsource the design and printing services on a case-by-case basis.

In a recent article titled ‘Should hospitals invest in customised on-demand 3D printing for surgeries?’, published in the International Journal of Operations & Production Management, we illustrate some of the positive outcomes of using 3D printing for surgeries and the mechanisms by which those are generated.

3D printing for surgeries reduces the time from recommendation of the surgery to the surgery date, and surgeries with durations of four to eight hours are reduced by 1.5 to 2.5 hours if patient-specific instruments are used (they are even 25 to 30 minutes shorter if only an anatomical model is used to plan surgery). It can also reduce variability in surgical outcome, including less anaesthesia and related risks, less bone removal and shorter recovery time for patients – e.g., a patient is able to walk one to two days after surgery, compared to three to four days without 3D printing.

The research team has developed frameworks that will aid hospitals in their decisions to invest in 3D printing. Our research shows the decision to implement 3D printing in hospitals, or to engage service providers, will require careful analysis of complexity, demand, lead-time criticality and the hospital’s own objectives. Hospitals can follow different paths in adopting 3D printing for surgeries depending on their context.

Systematic assessment

I believe there is a need for systematic assessment of the surgical procedures, which can benefit from use of 3D printed anatomical models, customised surgical guides and implant production. These can be rolled out across multiple NHS trusts.

Data should be collected to assess the impact of technology in improving hospital efficiency and clinical outcomes. This may open up opportunities for training of surgeons on the procedures.

Overall, this research demonstrates that 3D printing should be considered by all hospitals and healthcare providers, and it shows that patient experience and outcome, as well as hospital efficiency, could be improved.

More information on Dr Chaudhuri's research interests.

/prod01/channel_3/business/media/durham-university-business-school/impact/Home-Header-or-Footer-(12).png)