Freedom of thought requires freedom of movement

By Dr Jana Bacevic

23rd June 2025

This sentence, for me, sums up why mobility – and open borders – are essential to thinking, and to knowledge. My friend and collaborator Jana Schmidt said this in one of the conversations I curated for The Philosopher, UK’s longest-running public philosophy journal, on the topic of ‘Thinking together’. The series itself was titled ‘How to think together’, and it arose from work and the conversations with people during my research leave in Easter (Spring) 2023, at the Hannah Arendt Center at Bard College, New York. This blog post, however, is about my most recent research leave, at the Institute for Practical Ethics at University of California-San Diego.

Research leave (or sabbatical, as it’s more commonly known in the US and some other systems), is the periodical leave academics get from teaching and administrative duties to focus on research (or, in my case, thinking). Durham University has a pretty good entitlement, one term for every six; some departments/academics will wait until they have accrued a full year, while some prefer to take them as they come. Some academics stay at home, focusing on writing or data collection or whatever other element of academic work ends up side-lined by the demands of day-to-day teaching, administration, and caring duties.

For me, however, staying put was never an option: my academic trajectory was fundamentally shaped by the desire to learn about the world in its different shapes and forms, and so intertwined with mobility. I enrolled in undergraduate studies of anthropology (after seeing the quote from Thomas Hylland Eriksen that “Anthropology is philosophy with the people in”), both because it seemed the broadest of disciplines – integrating elements of psychology, sociology, history, and biology – but also, and more importantly, because it had an interest in the Other-than-self (studying in Serbia, with its history of Yugoslav socialism, internationalism, and non-alignment, meant academic anthropology was very critical of colonisation and other ‘meta’ narratives). From there, I went to England, then to Hungary (the Central European University in Budapest), then to Denmark, passing through New Zealand, eventually coming back to England, first to Cambridge and then Durham.

There are different ways to go about academic mobility, of course. Some people see this as an opportunity to acquire something (knowledge, experiences, intellectual or social capital) which they can then take with them (and presumably trade/exchange). This is an approach I refer to as extractivism: it sees others – places, people, non-humans – as primarily something to extract from. By contrast, I tend to think of movement as part of life, which is built not through what we acquire (a title, a job, a house, a car, even a partner/children), but through encounters with others – and how we can make and change things through these encounters, including ourselves.

This is doubly important because unnecessary travel, especially by people and from countries of the Global North, generates carbon emissions that compound the climate crisis. Of course, one may observe that, compared to the pollution generated by the fossil fuel industry, or industrial agriculture, one small academic trip does not make much difference. But it is precisely this tendency to exempt ourselves from ethical and moral requirements we apply to others – the failure to observe Kant’s categorical imperative in practice – that I find so interesting. My current research project ‘Uncategorical imperatives: understanding non-reciprocity’ (funded by the Leverhulme Trust) explores this question: can we account for people’s moral inconsistency while retaining a commitment to social justice?

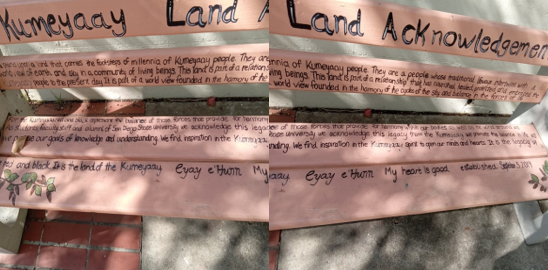

During my stay at UCSD, I gave a lecture on this topic, entitled “What do we not owe others? Reciprocity, debt, and injustice in the post-Anthropocene”. I opened the talk with a land acknowledgment: the University of California – San Diego sits on unceded Kumeyaay land. Prior to the talk, I had stopped by UCSD’s Intertribal Center to check in with the people there how to use the land acknowledgment. Land acknowledgments can be tricky – not only because they remind settlers of the often violent process of dispossession by which the land came to its present political form, but because they challenge the (Western, capitalist) concept of ownership as the basis of rights: after all, the Kumeyaay refer to themselves as stewards of the land, not its proprietors. To me, this feels much more natural.

1: A bench with Land Acknowledgment, SDSU campus. Photo: J Bacevic

This, of course, is not the only way in which indigenous presence is felt in San Diego: it is a living part of local culture, perhaps more visible than in some other parts of the US. The city’s Chicano Park is a lasting visual monument to Chicanx resistance. The student union of the other campus in San Diego I visit, the San Diego State University (SDSU), is called ‘Aztec’, just like the SDSU’s sports team. And on the main UCSD campus stands an artistic rendering of a totem pole, named ‘Sun God’, who watches over us as we sit on, walk around, or cut across the lawn named after him.

2: Sun God, Nikki St Phalle, UCSD campus. Photo: J Bacevic

On one of my days off, I visit the Museum of Us – an apt, in my view, renaming of the former Museum of Man – and the exhibition Hostile Terrain ’94 , which documents the harms produced by US Border Patrol’s ‘Prevention through Deterrence’ policy introduced in 1994. So far, it has resulted in 3,200 migrant deaths – and the exhibition documents both their location and names/age for those who have been identified.

3: Hostile Terrain 94, Museum of Us. Photo: J Bacevic

Death is not all that occurs at borders, though. As the part of the exhibition curated by the O’odham Anti-Border Collective reminds us,

“The O’odham have inhabited a continuous are of land for thousands of years in what is known to some as the Southwest United States and Northwest Mexico but is called in O’odham the jewed (homelands) …This land is home to O’odham ancestors (huhugam), current O’odham people, and future generations (…) This exhibition urges us to remember that the land is not hostile, Indigenous peoples have lived in the Sonoran Desert since time immemorial. It is the border policies and associated colonial practices that are hostile”.

The violent clash between nation states’ border regimes and the lived reality of freedom of movement strikes particularly clearly while I am in San Diego. There are protests both on and off-campus against increased criminalization of migrants. On March 8th, International Women’s Day, I join one of the local community groups protesting in front of the local Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE). On the same day, Mahmoud Khalil is arrested in New York. As I take my daily bus and sometimes tram (‘trolley’) to the UCSD campus, passing by the beautiful La Jolla shore, I follow and watch newsreels about the Trump administration unleashing a full frontal attack on all institutions and forms of life it finds inimical to its programme. This includes higher education and immigration, as well as, of course, their intersection; it will not be long until we will hear the first news about students’ visas revoked and students deported, alongside a campaign against DEI and cuts to funding for research on climate change, gender, and history that does not hide the violence of racism and settler colonialism.

On the ‘home front’, as the migrant members’ representative in Durham University and College Union, I am involved in a not too dissimilar a struggle: cuts to higher education across the sector mean our union has voted for strike action, which means assuring migrant members of their right to strike, alongside trying to develop a plan in case any of our staff are stopped and detained at the US border, as reports suggest happens to scientists with increasing frequency. As I write about the differences between the UK and the US, they happen against the backdrop of a broader convergence in world politics towards increasingly isolationist, extractive, and militarized politics that seek to make borders even more lethal.

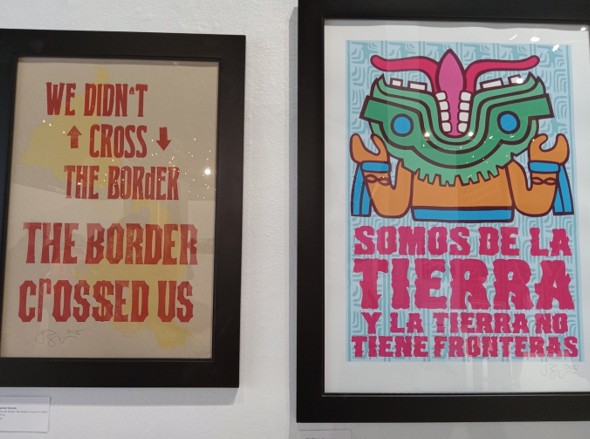

Yet, resistance always exists. On one of my last evenings in California, I visit the opening of the exhibition in the La Raza community center (where I volunteered briefly), called ‘Anti-border futures’. Put together by a collective of artists and curators, the exhibition is the final in a four-part instalment that engaged with the realities, harms, but also resistance to living with the border. The name reflects the belief that today’s practices of resistance are part of building and prefiguring a different future: one beyond borders. In the words of O’odham elders as well as the Zapatistas, ‘un mundo mas alla de las fronteras’.

4 Left: 'We didn't cross the border, the border crossed us'; Right: ‘Somos de la Tierra, y la Tierra no Tiene Fronteras”. Both: Jesus Barraza, Dignidad Rebelde, Anti-Border Futures exhibition, Centro Cultural de la Raza. Photo: J Bacevic

This is the thought on which I wish to end. Freedom of thought requires freedom of movement. But equally: without freedom of movement, there is no freedom of thought. This, for me, is what ‘academic mobility’ is fundamentally about: thinking, imagining, practising, and inhabiting a world where borders that have been imposed on us – be they of nation-states, languages, beliefs, disciplines, race, class, gender, bodies, or disciplines – no longer matter.

Find out more:

- Read about Dr Jana Bacevic and her work

- Visit our Sociology webpages for more information on our undergraduate, postgraduate programmes, and wider research areas

/prod01/prodbucket01/media/durham-university/departments-/sociology/SASS_Landscape_1.jpg)