Climate Targets and Emissions Realities - COP27

By Professor Minnerop

The 27th Conference of Parties under the 1992 United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) (COP27) and the 4th Conference of Parties serving as the Meeting of the Parties under the 2015 Paris Agreement (CMA4), are now in the second week in Sharm El-Sheikh. Daily messages range from good news, such as the fact that Loss & Damage has become an agenda item and that new funding pledges from eight governments have been made to the Least Developed Countries Fund (LDCF) and Special Climate Change Fund (SCCF) for some countries that are worst affected by climate change. Less optimistic messages relate to the observations that the international community displays huge inequalities at COP27, and the size of countries’ pavilions (wealthy countries tend to occupy more space) is only one facet of that, and that the world appears to be moving away from a “1.5°C focus”. Overall, there is a tangible and growing disconnect between the pavilion sphere in the “blue zone” (the “green zone” is even further away) where countries host meetings and events, and where NGOs demonstrate scientific research and solutions, and the real world of negotiations that will result in COP and CMA decisions. These decisions will be crucial for the implementation of the Paris Agreement, they will frame policy and law frameworks globally. Therefore, outcomes of these negotiations are what matters for keeping the 1.5°C temperature limit “alive”.

A number of reports have recently been published, on the current state of affairs of greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions trajectories and remaining carbon budgets commensurate with various future temperature scenarios. As negotiations are under way, these reports are far from painting a positive picture. Hopes are that COP27 can be the “implementation” or even the “Loss & Damage” conference and will not be the “gas deal” summit in the memory of UNFCCC COPing history.

The following shares, in a nutshell, some findings and recommendations of various reports, weaving in some reflections. The reports covered include the Working Group I contribution to the Assessment Report 6 (AR6) and the Special Report on Global Warming of 1.5°C, the UNEP Emissions Gap Report 2022, the Synthesis Report of the UNFCCC Secretariat for Long-Term Low Emissions Development Strategies (LT-LEDS) and the Global Carbon Budget Report 2022.

This is followed by some final remarks on the role of the Global Stocktake (GST), the Paris Agreement’s central oversight mechanism that assesses the collective progress of Parties.

The Paris Agreement, in implementing the UNFCCC, aims at decarbonising economies world-wide. It is the first multilateral environmental agreement that explicitly calls for a limitation of global temperature increase of well below 2°C, ideally closer to 1.5°C. If decarbonisation of all sectors and at all organisational levels of societies can be achieved globally, the goal of limiting global temperature increase remains within reach.

The state of affairs: GHG Emissions at the beginning of COP27

In its latest Emissions Gap Report 2022, the United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP) warns “that the window is closing”, and that the climate crisis calls “for rapid transformation of societies” in a world that “is still falling short of the Paris climate goals, with no credible pathway to 1.5°C in place.” Among the key messages of the report is that the newly submitted and enhanced Nationally Determined Contributions (NDCs), submitted since COP26/CMA3 in Glasgow, only represent less than one per cent of additional emissions reductions by 2030. This includes consideration of all GHG emissions and not just CO2 emissions (major GHGs are carbon dioxide (CO2), methane (CH4) and nitrous oxide (N2O), other powerful GHGs include hydrofluorocarbons (HFCs), perfluorocarbons (PFCs) and sulphur hexafluoride (SF6)).

Targets fall below the necessary standard and policies are often insufficient, not credible, or entirely absent. The UNEP report identifies a widespread lack of implementation plans for targets for all types of emissions. The G20 members in particular are failing to provide credible implementing plans for their 2030 targets. The findings confirm the IPCC’s conclusions in the IPCC Special Report on Global Warming of 1.5°C that was already published in 2018. According to the IPCC, global warming based on current pledges was at the time expected to surpass 1.5°C above pre-industrial levels, even if national commitments would increase in scale and ambition after 2030. This has not changed under current pledges and policies.

The Working Group I contribution to IPCC AR6 confirmed that under all GHG emissions scenarios, including for a low emission trajectory, global warming of around 1.5ºC will occur around 2040, based on the best estimated, as indicated in the table below.

|

Near term, 2021–2040 |

Mid-term, 2041–2060 |

Long term, 2081–2100 |

||||||

|

Scenario |

Best estimate (°C) |

Very likely range (°C) |

Best estimate (°C) |

Very likely range (°C) |

Best estimate (°C) |

Very likely range (°C) |

||

|

SSP1-1.9 |

1.5 |

1.2 to 1.7 |

1.6 |

1.2 to 2.0 |

1.4 |

1.0 to 1.8 |

||

|

SSP1-2.6 |

1.5 |

1.2 to 1.8 |

1.7 |

1.3 to 2.2 |

1.8 |

1.3 to 2.4 |

||

|

SSP2-4.5 |

1.5 |

1.2 to 1.8 |

2.0 |

1.6 to 2.5 |

2.7 |

2.1 to 3.5 |

||

|

SSP3-7.0 |

1.5 |

1.2 to 1.8 |

2.1 |

1.7 to 2.6 |

3.6 |

2.8 to 4.6 |

||

|

SSP5-8.5 |

1.6 |

1.3 to 1.9 |

2.4 |

1.9 to 3.0 |

4.4 |

3.3 to 5.7 |

||

Credit: WG I, IPCC AR 6

Median estimates for total emissions under current unconditional NDCs range between 52–58 GtCO2e yr−1 in 2030. According to the IPCC and UNEP, this is nearly double the amount that would keep the world on track for a pathway for maintaining 1.5°C with no or only limited overshoot. Without additional ambition, the amount of time that is left to ensure that temperature levels can be stabilised around 1.5°C is reduced further.

Of particular concern are the emissions caused by increasing consumption of coal, oil and gas. The Global Carbon Budget Report 2022 provides in its latest report specific data on emissions that are directly linked to CO2 emissions caused by fossil fuel consumption. It reveals that “emissions from coal, oil, and gas in 2022 are expected to be above their 2021 levels (by 1.0 %, 2.2 % and −0.2 % respectively). Regionally, emissions in 2022 are expected to have decreased by 0.9 % in China (3.1 GtC, 11.4 GtCO2) and 0.8 % in the European Union (0.8 GtC, 2.8 GtCO2) but increased by 1.5 % in the United States (1.4 GtC, 5.1 GtCO2), 6 % in India (0.8 GtC, 2.9 GtCO2), and 1.7 % in the rest of the world (4.2 GtC, 15.4 GtCO2).”

Relating Emissions to Temperature Predictions

Taken together, the current unconditional NDCs only provide a chance of 66 per cent to limit global warming to about 2.6°C by the end of the century. For conditional NDCs, the temperature increase could be limited to 2.4°C. These conditional, more ambitious elements of NDCs will only be implemented by Parties that include these conditions in their NDCs, if the Parties are provided with financial means, capacity building support, and technology and knowledge transfer, in addition to access to a functioning carbon market.

If current NDC targets and corresponding policies are not strengthened, however, a temperature increase of 2.8°C towards the end of the century is most likely. Thus, to meet the Paris Agreement’s objectives, deep GHG emissions reductions must be achieved, at unprecedented levels, up to 2030. So far, existing policies would achieve emissions reductions of an estimated 5 per cent (unconditional) and 10 per cent (conditional) by 2030. Bringing emissions back to a least-cost pathway for limiting the temperature increase to 1.5°C (an orderly transition), deeper reductions of 45 per cent by 2030 are necessary. This means that if an emissions scenario of the IPCC is still envisaged, most and rather deep emissions reductions foreseen by 2050 must necessarily occur after 2030. This delay continues to risk a low-cost transition and it shifts the burden of making these GHG emissions reductions to the younger generation.

Recommendations for Deeper Reductions

The following key actions are set out in the UNEP Report:

- Avoiding lock-in of new fossil fuel-intensive infrastructure.

- Further advancing zero-carbon technologies, market structures and planning for a just transformation.

- Applying zero-emission technology and behavioural changes to sustain reductions to reach zero emissions.

- Reforming food systems, including demand-side dietary changes (tackling food waste), protection of natural ecosystems, improvements in food production at the farm level and decarbonization of food supply chains.

This global transformation to a low-carbon economy is estimated to require investments of at least USD 4-6 trillion a year. Funding at this scale can only become available if finance flows, from both the private and the public sector, are made consistent with a low-emission economy, as Article 2 paragraph 1 literature c of the Paris Agreement stipulates (“Making finance flows consistent with a pathway towards low greenhouse gas emissions and climate-resilient development.”). The financial system itself must undergo change in structure and processes, including central banks, commercial banks, institutional investors and other financial actors.

Recommendations for Integrated Reform of the Finance Sector

UNEP recommends six approaches to financial sector reform to be “carried out in an integrated manner”:

- Make financial markets more efficient, including through taxonomies and transparency.

- Introduce carbon pricing, such as taxes or cap-and-trade systems.

- Nudge financial behaviour, through public policy interventions, taxes, spending and regulations.

- Create markets for low-carbon technology, through shifting financial flows, stimulating innovation and helping to set standards.

- Mobilize central banks: central banks are increasingly addressing the climate crisis, but more concrete action on regulations is urgently needed.

- Set up climate “clubs” of cooperating countries, cross-border finance initiatives and just transformation partnerships, which can alter policy norms and change the course of finance through credible financial commitment devices, such as sovereign guarantees.

In addition, the IPCC confirmed in its Special Report on Global Warming of 1.5°C that demand-side measures are key elements of 1.5°C pathways. This includes lifestyle and economy wide choices that lower energy demand and reduce energy intensity of all sectors. These choices must be supported through investment and incentives. By 2030 and 2050, all end-use sectors (including building, transport, and industry) would be required to demonstrate their energy demand reductions in modelled 1.5°C pathways, and ensure that these are comparable and beyond those projected in 2°C pathways. Transition plans and implementing polices with interim targets are key to achieving this. Parties to the Paris Agreement recognised this already in 2015 when they adopted the treaty. Under the Paris Agreement, Parties are not only under the obligation to submit improved and more ambitious targets every five years, they are also expected to submit plans that detail how they intend to achieve their targets.

The Benefits of Long-Term Low GHG Emission Development Strategies (LT-LEDS)

In accordance with Article 4, paragraph 19, of the Paris Agreement, Parties must formulate and communicate long-term low GHG emission development strategies.

COP21 in Paris invited Parties (decision 1/CP 21, paragraph 35) to communicate, by 2020, long-term low GHG emission development strategies. Last year, the COP serving as the meeting of the Parties under the Paris Agreement (CMA) at its 3rd conference (COP26 was also CMA3, and COP27 takes place alongside CMA4) urged Parties that have not yet done so to communicate, by CMA4, long-term low GHG emission development. These strategies are expected to reflect latest scientific evidence.

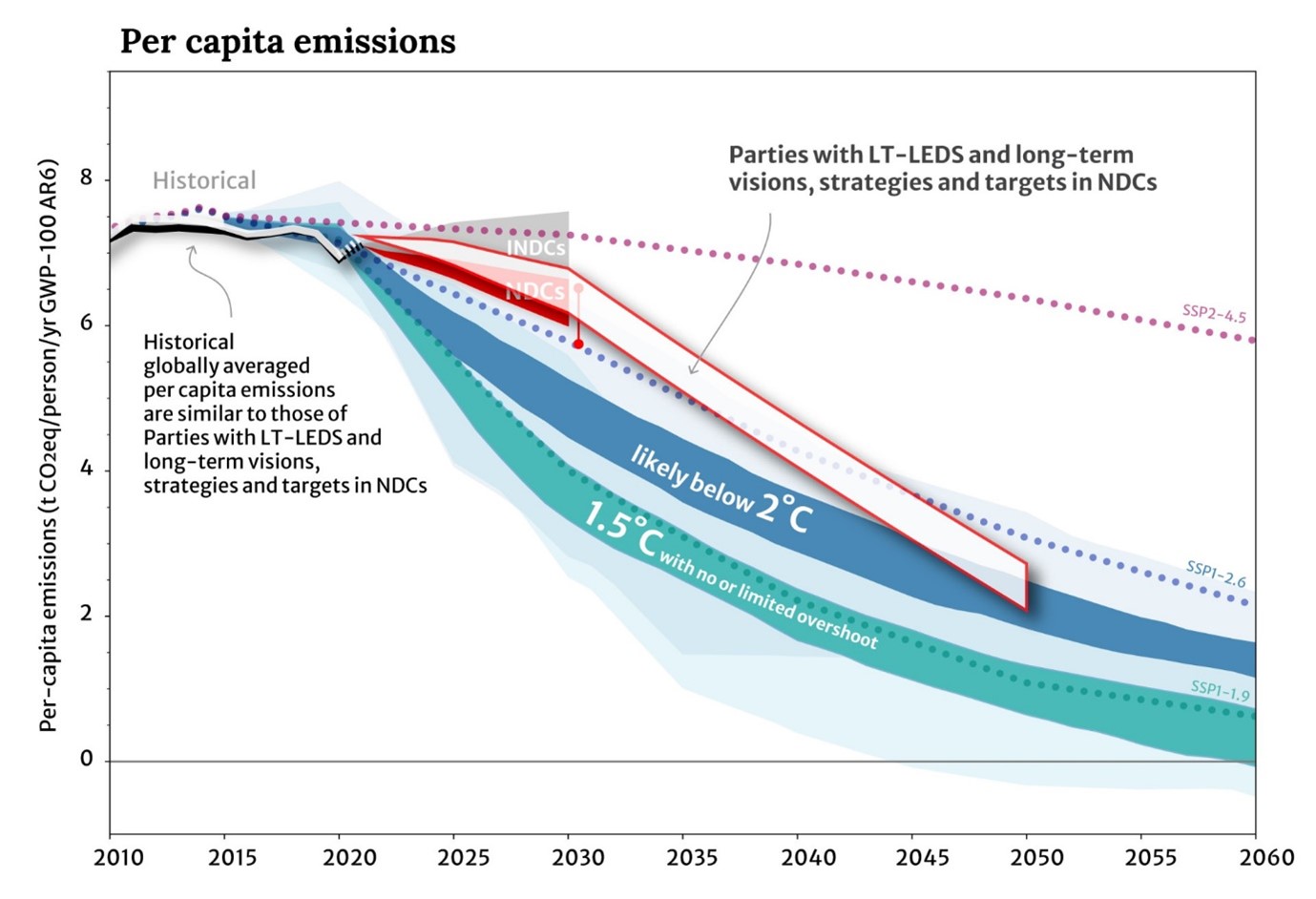

So far, only 56 submissions were received. Based on the communicated LT-LEDS and quantifiable information on long-term visions, strategies and targets of Parties that have provided this information in their latest NDC, emissions are estimated to be 6 (2–11) per cent lower in 2030 than in 2019. Apart from aligning per-capita emissions more closely with the low-cost temperature scenario as the graph below illustrates, LT-LEDS bring a number of synergies for transitioning societies. Take-away points from the Synthesis Report of the UNFCCC Secretariat for LT-LEDS are that 91 per cent of submissions indicated that there are synergies with economic growth, 83 per cent state synergies with job creation, and 75 per cent point out that positive effects are achieved for social welfare and human well-being with reduced inequalities. Furthermore, 75 per cent report improved business and industry competitiveness, and 72 per cent state better human health including through improved air quality, and the same percentage of submissions outlines positive effects for sustainable cities, while 68 per cent mention synergies with climate resilience and disaster risk reduction.

These percentages indicate that transforming societies into low-emissions communities at scale is beneficial to achieve other desirable outcomes. These outcomes correspond to several Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), including SDG 8 (decent work and economic growth), SDG 17 (partnerships for the goals), SDG 9 (industry, innovation and infrastructure), SDG 10 (reduced inequalities), SDG 11 (sustainable cities and communities), SDG 3 (good health and well-being), SDG 4 (quality education) and SDG 12 (responsible consumption and production).

A different way for economic and societal development is, thus, available. Conversely, following the pathway of development through fossil fuel consumption, albeit this being the choice of the past and the “western world”, increases costs both for the (unavoidable) transition and for (increasing) consequences of climate disruption. Development through fossil fuel consumption should, in the light of the scientific evidence – including the evidence from social sciences – no longer be perceived as the preferred, let alone the only, path for economic growth or societal well-being. Alternative pathways for successful progress exist and the narrative for socio-economic growth has changed. Further delays in the transitioning process will amplify challenges that are mentioned in the LT-LEDS by Parties.

Credit: UNFCCC

The graph illustrates the extent to which LT-LEDS support Parties’ alignment with low-cost emissions trajectories.

Concluding Reflections on the Specific Role of the Global Stocktake as Treaty-based Mechanism

Taken together, these reports concretise and confirm existing trajectories and scientific evidence, and outline very similar predictions for global GHG emissions under current NDCs and available policies. Can the Global Stocktake (GST) make an additional contribution and go beyond another reporting exercise, so that it facilitates transformational change at scale and in a timely fashion?

The GST aims to periodically take stock of the implementation of the Paris Agreement to assess the collective progress towards achieving the purpose of the Agreement and its long-term goals. It sets out to do that in a comprehensive and facilitative manner, considering mitigation, adaptation and the means of implementation and support as main thematic areas, in the light of equity and the best available science. The first GST started at COP26/CAM3 in Glasgow and is set to conclude at COP28 in 2023. It shall inform Parties in updating and enhancing their actions and support in accordance with the relevant provisions of the Paris Agreement, as well as in enhancing international cooperation for climate action.

The GST is a Party-driven process but open for input of non-Party stakeholders, such as NGOs with observer status. The main difference between existing reports and the stock-taking process of the Paris Agreement is that only the latter process is treaty-based. All other reports provide best available scientific evidence, however, they are produced in fora that are external to the Paris Agreement. Even if the latest scientific evidence in IPCC reports is framed in unequivocal terms, Parties can choose to merely welcome “the timely completion” of a report, instead of welcoming the report itself. This happened at COP24 in 2018 for the IPCC Special Report on Global Warming of 1.5°C, even though Parties had invited this report (FCCC/CP/2018/10/Add.1, para. 26). The language matters and signals the degree of political endorsement.

The GST adds a treaty-based mechanism that could function, if well-designed and effectively implemented, as a transmission belt for existing reports and further sources of inputs specifically to the GST, as specified in Decision 19/CMA.1. Parties are obliged to demonstrate how the preparation of their NDC has been informed by the outcomes of the GST, in accordance with Article 4, paragraph 9, of the Paris Agreement. This is crucial for the ratcheting up mechanism that the Paris Agreement establishes. From an international law point of view, the principle of good faith in treaty implementation must guide Parties in observing the outcomes of the GST and in turning the evidence derived from the outcomes of the GST into enhanced ambition. This principle of good faith is paramount to the functioning of international law. Further research is carried out at Durham Law School to establish Parties’ legal obligations in respect of observing the outcomes of the GST.

/prod01/prodbucket01/media/durham-university/departments-/law-school/37038.jpg)