Anthony Payne - A Fond Reminiscence

Anthony Edward Payne was an English composer, music critic and musicologist. He died at the age of 84 on 30 April 2021. Professor Jeremy Dibble (Department of Music) has shared his memories.

I was much saddened to hear of the death of my friend, distinguished composer and musicologist, Dr Anthony Payne, on 30 April 2021. I first came across Anthony’s music in 1978 when I visited the Worcester Three Choirs Festival; his Ascensiontide and Whitsuntide cantatas (which completed a triptych begun with the Passiontide cantata of 1974) were premiered there and I can remember catching a glance of the 42-year-old composer at the end of the performance. I did not meet Anthony (or ‘Tony’ as we all knew him), however, until I was undergraduate composer in my final at Cambridge, working under Robin Holloway. Robin came up with the idea of inviting a number of his composer friends to Cambridge to meet his composer pupils and to talk about their music. So, in this way I had a chance to meet Oliver Knussen (whose magnificent Third Symphony had been performed at the Proms) and Tony whose song cycle The Stones and Lonely Places Sing had been recently performed by his wife, the soprano Jane Manning, and her ensemble Jane’s Minstrels. Although I can remember quite a lot about his talk, and Tony always an engaging speaker on music, our friendship was cemented by our mutual interest in the ‘British romantics’ as he called them, composers such as Elgar, Delius, Vaughan Williams, Frank Bridge and others. He was also intrigued to learn of my hopes of doing a PhD on the music of Hubert Parry.

After his schooldays at Dulwich College, where, incidentally, he befriended David Greer, Professor of Music at Durham between 1986 and 2001, he was an undergraduate at Durham from 1958 until 1961. During visits to Durham Tony would reminisce about his encounters with Arthur Hutchings, who had been appointed the university’s first resident Professor of Music in 1947. In coming to see the university for his interview, Tony met Hutchings in the Music School. He was invited to walk with Hutchings around Palace Green, after which Tony enquired: ‘When shall I have my interview?’ Hutchings rejoined: ‘You’ve just had it!’ Tony always spoke with great fondness of his three years at the university and how it had shaped so much of what he had learned about music. Besides the imposing presence of Hutchings, one of the most formative influences was that of the late Peter Evans who was a music lecturer until he left to become Professor of Music at the newly inaugurated Music Department at Southampton University in 1961. (He also became my PhD supervisor when I left Cambridge for Southampton in 1980.) After leaving Durham, he forged his way initially as a freelance musicologist, writing for magazines and newspapers, particularly on those subjects for which he had great enthusiasm. This he later combined with a career as a composer.

In the years after Southampton, I got to know Tony’s books on Schoenberg, Frank Bridge and the Delius entry he wrote for the latest edition of Grove’s Dictionary of Music and Musicians. I also heard him speak on the radio, especially about his passion for Vaughan Williams’s Fantaisa on a Theme of Thomas Tallis which he greatly admired. But I was not in touch with Tony much until around 1995 when the BBC, in marking the tercentenary of the death of Henry Purcell, instigated a year-long celebration of British music from across the centuries. I had occasion to take on the challenging task of editing Parry’s Piano Concerto which the BBC broadcast during that year and which Hyperion Records promptly recorded soon after. I received an lengthy and effusive ‘phone-call from Tony asking me about the concerto, the book I had published on Parry in 1992 and my forthcoming work on Charles Villiers Stanford. It was from this time that we began to get to know each other better. By this time, of course, we shared something on common since I had been appointed a lecturer in music at Durham in 1993. Tony then made various visits to Durham. MUSICON, the university’s professional concert series featured some of his music and met various composition students in the Music Department and gave advice and guidance on their work. We also had the chance to talk about our mutual interests in British music and it was such an edifying pleasure to do this when he came to stay in our Coxhoe home.

One of Tony’s preoccupying interests, which combined his skills as a composer and musicologist, were the surviving sketches of Elgar’s Third Symphony, a work which the BBC had commissioned in the early 1930s and on which Elgar was working, on and off, when he died in 1934. Elgar left mixed messages about what he wanted to be the fate of his sketches after his death, and the general feeling was at the time (a fact articulated in the publication of over forty pages of the sketches in William Reed’s book Elgar as I knew him in 1936) that their realisation into a finished work would be impossible. Some attention to the symphony’s sketches was given by the BBC in the 1970s, but then it was thought unethical to ‘tinker’ with the materials and so the project was dropped. At much the same Tony had developed a serious interest in Elgar’s unfinished work and he took part in a workshop which the BBC instigated in 1993 where his work on the sketches featured prominently. In fact, by this time, Tony had, more or less, completed the first three movements of the symphony, but he was faced with the greater problem of the finale for which Elgar had left fewer indications about the structure and the work’s conclusion. In the end, however, Tony realised that it would require a fair amount of his own compositional intervention, but, given his own comprehensive understanding of Elgar’s distinctive language, he was able to do this with reference to Elgar’s other late works such as the Nursery Suite, completed in 1930. Trusting his own intuition, he went ahead and completed the last movement. Performances of the finished work began in September 1998 and very soon the work was being played by international orchestras across the world. In talking to Tony, now in his early sixties, he admitted to me that his work on the Elgar symphony, enhanced by the publication of the score and recordings of the work and his discussion of the sketches, had transformed his career.

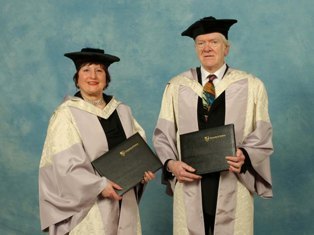

In 2007 Durham University celebrated the 175th anniversary of its foundation in 1832. As part of MUSICON’s participation in the year’s events, the BBC Philharmonic came to Durham for a two-day visit, first to give an orchestral concert on 6 February in the cathedral (under the direction of Martyn Brabbins), and, second, to accompany of a choir of Durham students and the cathedral choir in choral evensong on 7 February for BBC broadcast. It seemed entirely appropriate that the orchestral concert should feature music by composers on whom Durham had conferred the honorary degree of D.Mus. and so, with this criterion in mind, Arnold Bax’s symphonic poem, Tintagel, and William Walton’s Viola Concerto were chosen. It also seemed the ideal chance for the university to confer the degree on both Tony and his wife and to include Elgar’s Third Symphony in the programme.

On the day of the concert, I felt especially proud to give the oration for both Tony and Jane in a ceremony in the Music School, one which also included a ‘question-and-answer’ presentation with Tony on the Third Symphony to an attentive audience. The concert was given to a packed cathedral, and the following day, people queued for a seat to hear choral evensong. This largely featured music by Hubert Parry (another Durham D.Mus.) but, at the end, as a closing voluntary, it also included Tony’s realisation of Elgar’s sketches of his unfinished Pomp and Circumstance March No. 6.

In the year after the conferring of his degree, I saw Tony at London’s Festival Hall where he and I both attended one of series of concerts of to mark the fiftieth anniversary of Vaughan Williams’s death in 1958. The concert, conducted by Richard Hickox (who had also received an honorary D.Mus. from the university in 2003), received a standing ovation form the large and appreciative audience, one which Tony found especially moving given his particular admiration for Vaughan Williams’s music. I also saw him in 2012 when we were both present at the British Library for the conference marking the 150th anniversary of Delius’s birth in 1862. By that time, I had begun to have ideas for a book on Delius’s music which we discussed together, though I was not able to begin serious research until some years later. It was at the forefront of our conversation when Tony, now a spritely 80, came to Durham in 2016 to hear a performance of his new Piano Quartet played by the Primrose Piano Quartet at another MUSICON concert. It had very much been my hope that Tony would have been able to read my book on Delius, due out in June this year, but this was not to be. However, notwithstanding this tinge of regret, I hope very much that his life in music, and that of his wife, will receive their due acknowledgement. Tony was a fine composer, an engaging speaker and original thinker about music. Though his presence will be greatly missed, he has left us a rich creative legacy for which we must all be grateful.

/prod01/prodbucket01/media/durham-university/departments-/music/45088-2-2100X942.jpg)